We all have our cultural lodestars, those creators of books, films, poems, plays and music that have seduced us entirely. We can often recall, with pinpoint precision, our first encounter with them, the moment a lifelong passion was born. Forty years ago, this happened for me with the work of Eugene Ionesco.

It began with La Cantatrice Chauve, his first and best-known play, which I was introduced to by a particularly cool French teacher at school in Worcestershire. Ionesco’s wordplay and anarchic wit hooked me immediately, swiftly followed by the sharpness of his caricature. Weaned on a diet of stodgy Middle England classics, this glimpse into new worlds thrilled me. Ever since, whenever I’ve seen that a Ionesco play is being staged somewhere, I’ve gone to see it, and never once been disappointed.

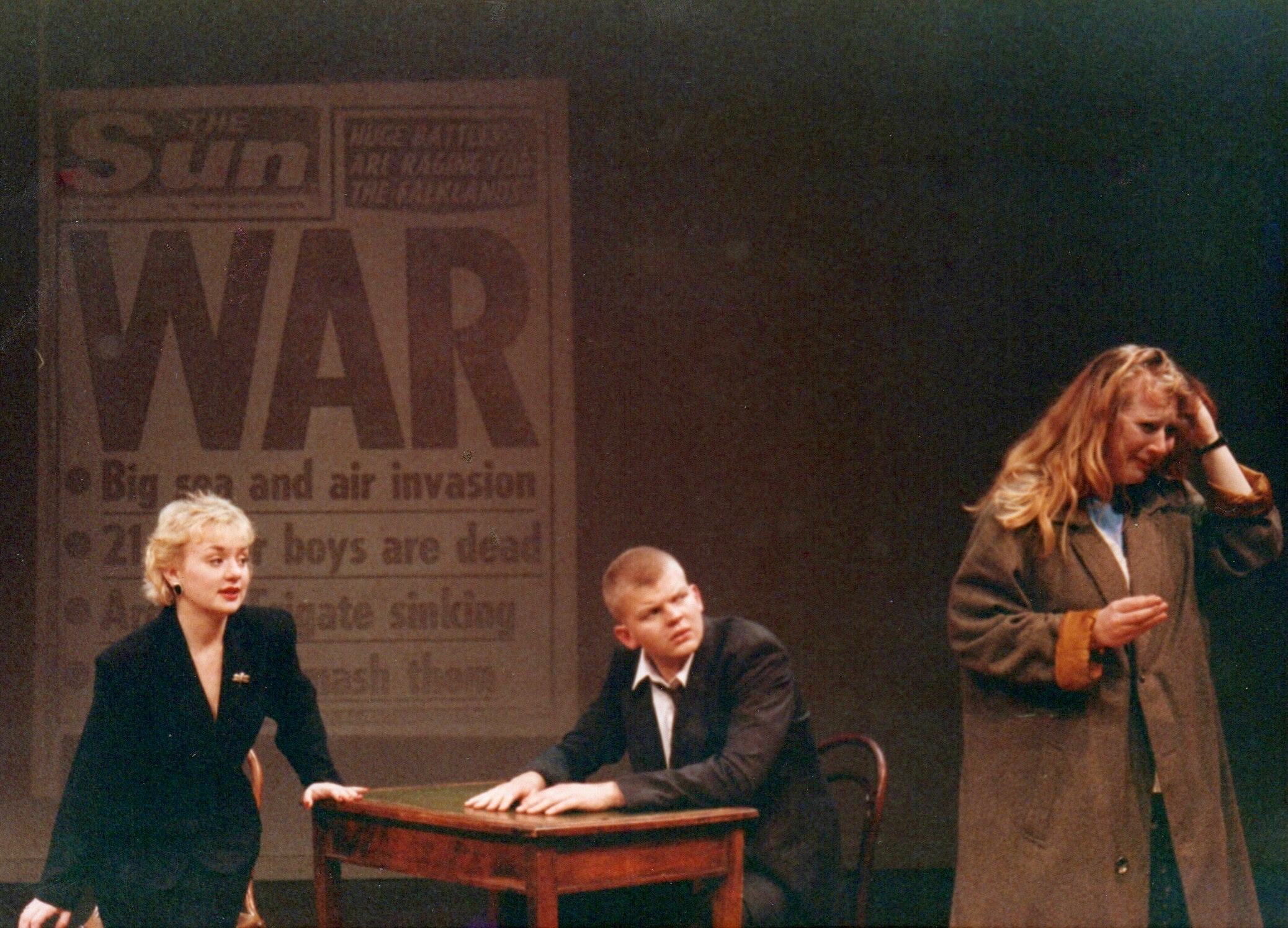

Studying drama at London University, I staged a version of Rhinoceros for my finals assessment. It wasn’t very good, though I loved getting to know the play better. His satire of spreading societal conformism, of hardening skins and hardening minds, was born of Ionesco’s own youth in the early 1930s, when his family had returned from France to his father’s native Romania, and he’d witnessed first hand growing Nazism, particularly amongst his University contemporaries. As he put it in a 1970 interview:

"From time to time, one of the group would come out and say ‘I don’t agree at all with them [the Fascists], to be sure, but on certain points, I must admit, for example the Jews ...’ And that kind of comment was a symptom. Three weeks later, that person would become a Nazi. He was caught in a mechanism, he accepted everything, he became a Rhinoceros."